We are the most connected generation right now, we have a realm of knowledge at our fingertips, and the psychological cost is a mind that never gets to rest. That’s not stress, that’s burnout. According to Psychology Today, Burnout is a state of emotional, mental, and physical exhaustion that is caused by workplace stress, and not being treated can bleed over into personal life. Most commonly it occurs in a workplace, but it can occur anywhere and should be treated as soon as possible.

History of Burnout:

Burnout was first discovered by psychologist Herbert Freudenberger in 1974. He described it as a loss of motivation, usually in one’s career as he observed in a volunteer clinic. His list was also very broad: “exhaustion, being unable to shake a lingering cold, suffering from frequent headaches and gastrointestinal disturbances, sleeplessness and shortness of breath,” as well as “quickness to anger,” paranoia, overconfidence, cynicism and isolation. Basically, burnout was everywhere and anything could be considered burnout. For instance, previously motivated and excited mental health workers experiencing burnout could start to feel weary and depleted, resenting patients and the clinic. He also related to them, as he was working long hours and had a lot to do, one day finding that he couldn’t get out of bed the day his family was supposed to go on vacation. Likewise, APS Fellow Christina Maslach from University of Berkley, California was one of the foremost researchers on burnout and studied extensive interviews from workers in the 1970s and her colleagues saw a similar trend; Workers often reported feelings of emotional exhaustion, negativity towards clients and patients, and crisis in feelings of professional competence. After her initial research Maslach published her findings in a 1976 publication called, “Burned Out” which would receive such a reaction from her audiences that would inspire more research, articles and attention from academic journals. In 2019, it became classified as a syndrome from WHO, rather than an illness. Today, Burnout is finally being understood as a medical condition, and is now accepted as one from mainstream medicine. It even has its own ICD-10 code (Z73.0). It can even qualify you for paid time off and other sickness benefits in some European countries, including Sweden. In countries like Finland, burnout can qualify people for rehabilitation workshops that include intensive group and individual activities, including counseling, nutrition, and exercise classes. Even though there has been increased awareness of burnout, there is still no official way to diagnose it and we can still hear traces of Freudenberger’s vague, catchall list of symptoms today.

Symptoms and Causes of Burnout:

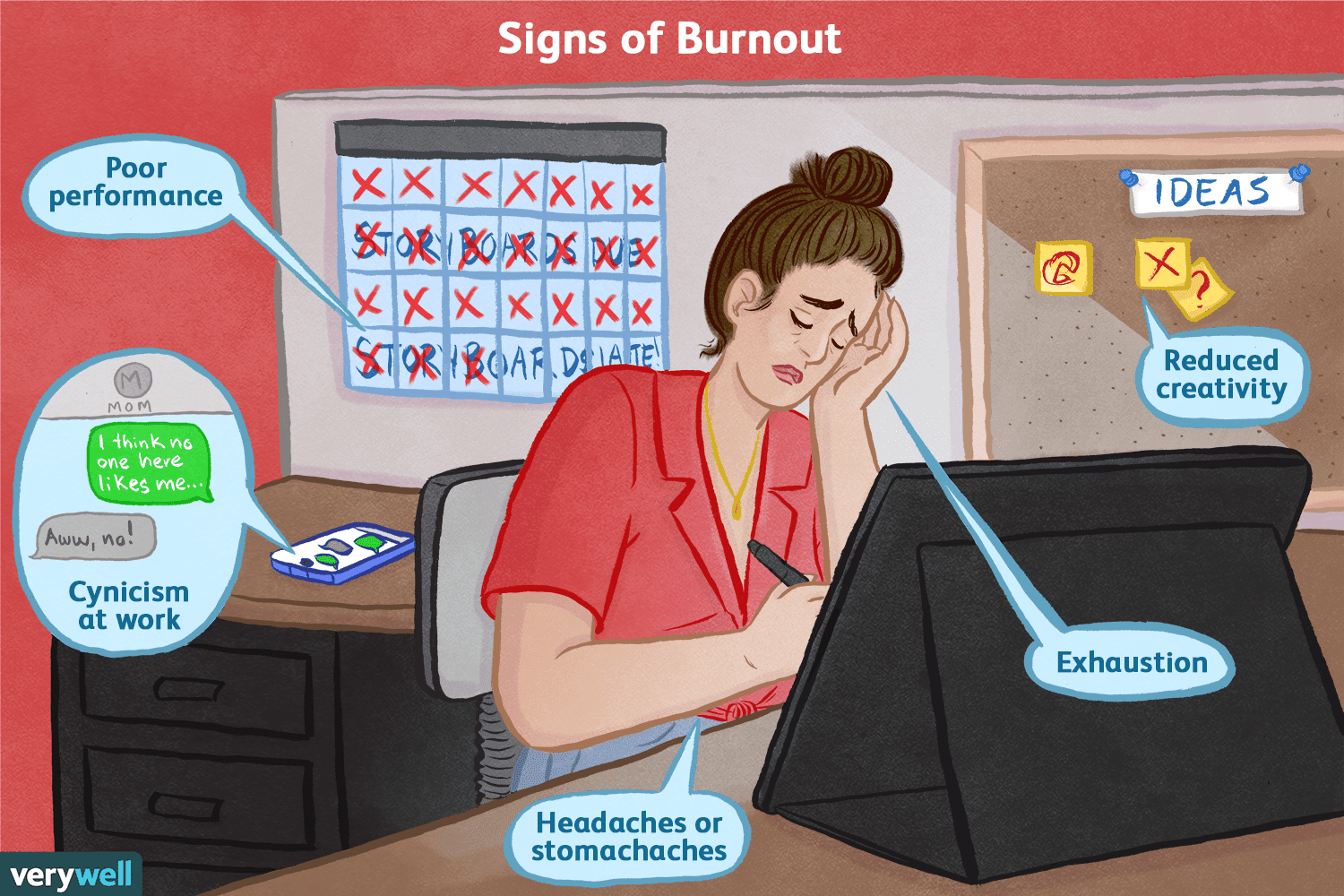

Burnout often shows up as a mix of emotional, physical, and behavioral changes that build slowly over time. People commonly experience constant exhaustion, irritability, and a growing sense of cynicism or detachment from their work or responsibilities. Motivation drops, tasks feel heavier than they should, and even small accomplishments stop feeling meaningful. Physically, burnout can bring headaches, muscle tension, sleep problems, and shifts in appetite or energy levels. These symptoms often lead to withdrawal, procrastination, and reduced performance, creating a cycle that makes everything feel harder than it used to.

Burnout is usually the result of multiple pressures stacking over time rather than one single cause. It often begins with chronic workload stress, where the demands placed on someone consistently exceed the time, energy, or resources they have to meet them. A lack of control—such as rigid schedules, unclear expectations, or limited autonomy—can intensify that strain. Emotional labor also plays a major role, especially in jobs that require constant empathy, patience, or conflict management. When people feel undervalued, unsupported, or disconnected from a sense of purpose, motivation erodes and exhaustion accelerates. Over time, this combination of relentless pressure, insufficient recovery, and a mismatch between effort and reward creates the perfect conditions for burnout to take hold.

A famous case:

A widely discussed example of burnout comes from a 2025 case study about Alex Reinhardt, the CEO of Kraftwerke Grün, whose collapse highlighted how even top executives can be pushed past their limits. After weeks of extreme workload and stress, Reinhardt fainted at his desk and was later diagnosed with exhaustion and dehydration, prompting concerns about his mental health and the unsustainable pace expected of high‑level leaders. His experience became emblematic of modern burnout: a mix of physical strain, emotional overload, and the cultural pressure to appear endlessly productive. The case sparked conversations across industries about the need for healthier boundaries, realistic workloads, and organizational responsibility in preventing burnout before it becomes a crisis. However, Reinhardt’s case isn’t the only case of burnout, it comes in many forms and addressing it before it becomes a crisis is vital for healthier workforces.

Conclusion:

Burnout has evolved from a loosely defined feeling of exhaustion in the 1970s to a globally recognized occupational phenomenon with real psychological, physical, and social consequences. Even as our world becomes more connected and efficient, the pressure to constantly perform has only intensified, making burnout not just a workplace issue but a widespread human challenge. The history, research, and modern cases all point to the same truth: burnout is preventable, but only when it’s acknowledged early and taken seriously. Understanding its symptoms, recognizing its causes, and creating environments that value rest, boundaries, and sustainable workloads are essential steps toward healthier lives and healthier organizations. As awareness continues to grow, so does the responsibility—both individually and collectively—to ensure that productivity never comes at the cost of well‑being.

Works Cited:

Frontiers | The Prevalence and Cause(s) of Burnout Among Applied Psychologists: A Systematic Review

Burnout: Symptoms, Risk Factors, Prevention, Treatment

Burnout and the Brain – Association for Psychological Science – APS

The history of burnout, from the 1970s to the Great Resignation – The Washington Post

Glossary:

WHO – The World Health Organization (WHO) is a specialized agency of the United Nations responsible for international public health. It sets global health standards, conducts research, provides guidance on diseases and health conditions, and supports countries in improving health systems and responding to health emergencies.

ICD-10 Code – The ICD‑10 code comes from the International Classification of Diseases, 10th Revision, a global diagnostic system created by the WHO. Each code represents a specific disease, condition, or health-related issue so that healthcare providers around the world can use a standardized language for diagnosis, reporting, and insurance purposes. For burnout specifically, the ICD‑10 code is Z73.0, which refers to “Burn-out: State of vital exhaustion.”